The Art and Science of Fashion, Illustrated

A Q&A on fashion illustrations from a major design house

I never considered myself a creative person growing up. Anything that required a tactile sort of skill I failed at miserably. Drawing, painting, sculpture. I’d stare in longing at classmates who could make an immediate impact with their art. I envied how their creativity was instantly understood and marvelled at. Though our instruments — chewed up no. 2s — were the same our art was absorbed at different timelines. As a child, the waiting differential to be understood felt agonizing.

What others could capture and convey instantaneously in a visual medium, I would need time and critical thinking in my observer to understand. Physically, there is nothing impressive about a pile of typed papers. The worlds I created weren’t suited for wading. To glance at. To skim. My worlds required an audience willing to take the time to dive.

As I got older and I grew an interest in fashion, new contours of envy took shape. In the glossy pages of magazines I pulled first from library shelves, then delightedly from my own mailbox when I was old enough to pay for my own subscription, I discovered genres of creativity that blossomed across multiple mediums. Not just the translation of imagination to paper. But that next step further into tangible creations. In the liminal space between the gaseous mental concept of a design in someone’s head to the wearable clothes they would become was the two dimensional interpretation of that vision to paper. I’ve always been fascinated by these illustrations and their tension in the space they occupy artistically. They are not photographs, nor portraits. They existed in the intermediary. An artistic interpretation of reality. Their dramatic proportions created space for the clothes to breathe. In these illustrations, the clothes were the protagonist - not the wearer. When I’d finished reading a magazine from opening editor’s letter to closing ad, I would cut out designer sketches and paste them into scrapbooks. When it came time to redesigning my own website - a place dedicated to the power and deeper symbols of fashion - I took a literal page from those stylish books and added this editorial element to the newly designed Taylor Swift Style to give the place I purveyed a Vogue-like touch.

📧 Email: This is going to get cut off in your inbox! This particular newsletter is best to view in app or in browser.

💟 Engagement Matters: If you’re not currently in a position to become a paid subscriber, please consider becoming a free subscriber + hitting the ‘🤍’ heart button on this post. Any/all engagement helps creators tremendously!

🖥️ Taylor Swift Style 2.0: In case you missed it, the blog got a complete makeover. I carefully thought through every aspect of the design so that you, too, could love it like it’s brand new. Some insight into that process below - including the fashion illustrations you see on the site.

Fashion is more than what we wear - it is the literal fabric of our humanity. It is identity. It is expression. It is politics. It is a sensory memory experience. Like the notes of a certain perfume or the lingering taste of an impeccably cooked meal, fashion is evocative and intrinsically tied to memory and to human history. The translation of fashion from a concept in the mind to a design on paper to a wearable feat of art and science for the body begins and ends with a sketch.

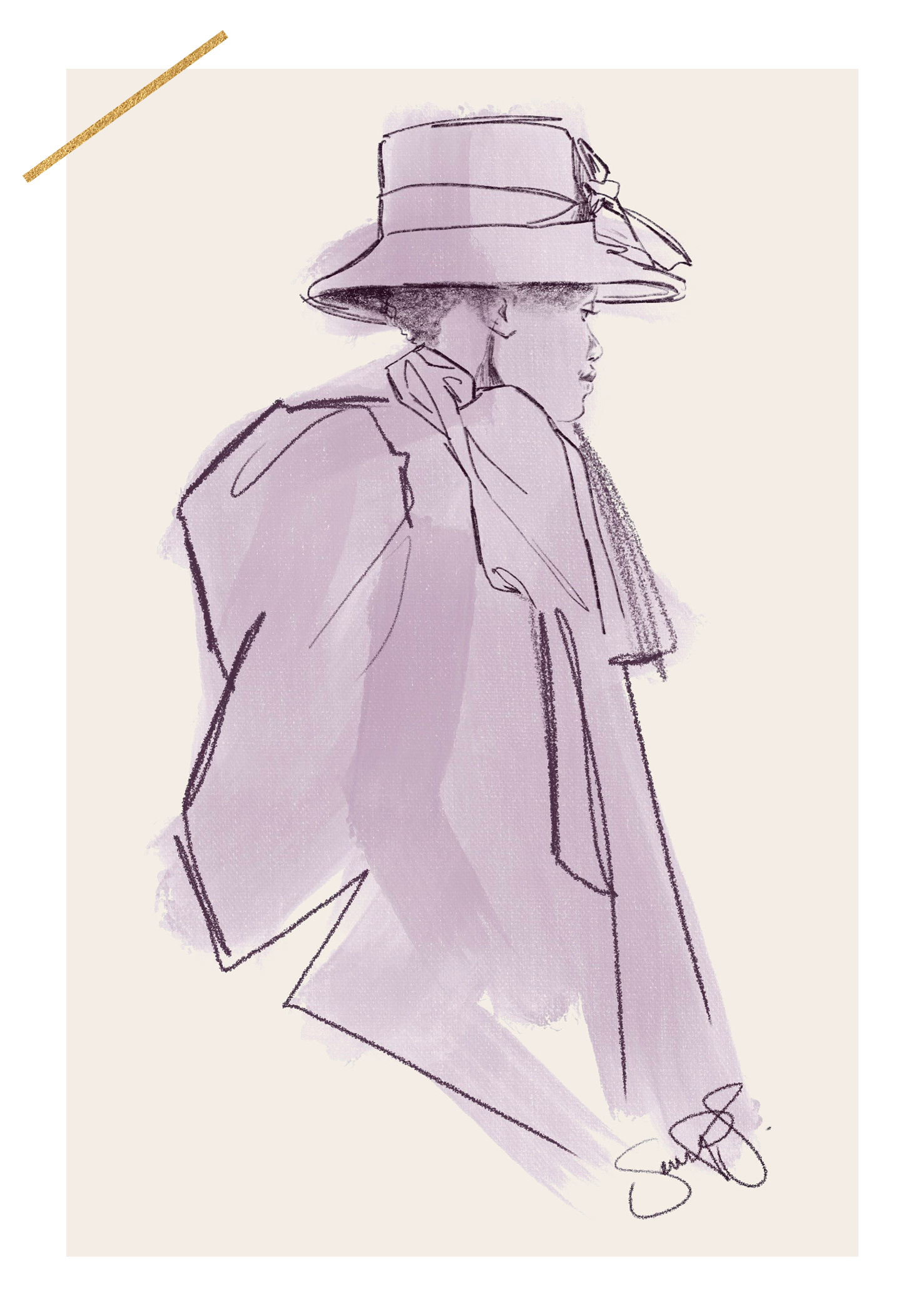

I recently spoke with Samantha, a fashion illustrator based in London. For the last decade, she’s worked her way up at a notable British fashion house. Her talent was such that the house created a role and an entire department dedicated to the art of fashion illustration when they realized how the changing times of technology necessitated it. I asked her to break down the process of fashion design, the role that fashion illustration plays in the process of creating clothes, and one of the most common questions I’ve been asked of why illustrations are styled the way they are.

💚 Editor’s Note: Our conversation has been edited and condensed for flow as well as to protect certain confidential designer information.

Sarah: Tell me a little bit about your role.

Sam: I’m a Senior Creative and Technical Illustrator and have been working in the field for the last decade. I collaborate with a few departments, including the teams that create the designer collections we present at Paris Fashion Week, bridal, couture, and all the VIP projects we have for celebrity clients.

For all these departments I do the technical drawings, sketches, and illustrations for external purposes. First, to the client in the early stages of when a garment is being designed. Then, to the media and press when a garment actually gets worn out by the client. It’s very technical and very artistic at different times of the day for completely different departments.

Sarah: How did you first get into fashion illustration?

I studied as a fashion designer first. For five years I studied costumes and fabrics in an artistic high school and then after that I did three years of specialty design at a fashion university school in Florence. During those years I was studying everything from pattern making to sewing to moodboards.

Eventually, in 2015, I moved to London for an internship at [a major British fashion house]. When you’re an intern, you’re basically there to help wherever and whoever you can. You do what’s necessary whether that’s patterns or drawings. I think from the beginning, [my managers] noticed that I was talented at drawing, so a lot of those tasks ended up coming my way.

This worked out well for me as even when I was in school what I enjoyed the most was illustrations. I like to say that I was at the right place at the right time as the industry was on the verge of changing in response to the demands of digital. A decade ago, fashion illustration wasn’t an established profession. Most fashion houses didn’t have the budget or even the foresight to consider illustration as a vital enough part of the design process to dedicate resources to it. Truthfully, I think it really only started to grow popular with the rise of social media. On the last day of my internship, [they] created a position for me as an illustrator.

When I left my home country of Italy to go to London I thought that it was for just a three month internship. Getting on the phone to tell my parents I was leaving for good was quite a shock. *laughs*

Sarah: What is it like working for a fashion house?

Sam: Something important to keep in mind is the DNA of the brand you’re working for. Even within a single house, there are often different personas or ‘clients’ that you are designing for.

Sometimes my work requires me to draw [the idea of a customer who] loves things that are a little more out there. Other times, I’m drawing to a much more sexy, feminine, or sultry vibe. All of these facets are still core to the concept of the brand - they are just executed in different ways. Being able to switch genres and flip between these fashion worlds and evoke different feelings on paper even within the same house has been pivotal.

Sarah: Fashion illustration, to me, seems to be both very artistic but also scientific. Would you agree?

Sam: Absolutely. To be a good fashion illustrator you need to not only be able to have a creative mindset but you also need a very strong knowledge of garment construction. Yes, it’s artistic but it’s also a very technical job.

Where I work most often is as an intermediary between the designer who represents the right or ‘creative’ brain of the operation and a pattern cutter who is the left half or ‘analytical’ side of the brain. I often say that pattern cutters are like the engineers of a garment. Pattern cutters are the ones who can tell you what is and isn’t possible. Every time I do a sketch, I check with them to see if something is achievable. I like to say that anything is possible on paper. I could draw a dress with wings if I wanted! But in order to make sure that everyone we work with is going in the same direction we need to work closely together to make sure that I am drawing something that is realistic and physically achievable.

Yes, it’s artistic but it’s also a very technical job.

An illustration is typically used to demonstrate to an external client how a garment will look when it’s complete. It’s much more artistic. But there are also technical drawings that we’ll give to production companies when it’s time to actually develop a collection. These technical or ‘flat’ drawings are used to understand what a garment looks like when you put things together. It’s like when you go to IKEA and you’re trying to understand how something in an instruction booklet is meant to look when it’s actually made. Everything in that garment from seams to darts to buttons is on that technical drawing.

Sarah: What is the process for coming up with a design?

Sam: I work with our designers very closely. For example, if I have to propose something for a client, the creative director and I will go over a brief submitted to us by a stylist. Stylists will often give us moodboards for a custom piece they are procuring for their client. In a fashion house, there are multiple teams who have to work in tandem to bring the vision on this moodboard to life in a way that satisfies the stylist, the client, and also our own heritage house codes.

Between designers, the creative director, pattern cutters, and myself there is a careful balance - a dance almost - in coming up with a proposal that goes in line with our brand DNA while also meeting the needs of the stylist and their client. In those brainstorm meetings, I have to get into the mind of the designer who is often speaking aloud their vision of the garment and I have to translate that into an initial sketch of a garment. A pattern cutter then acts as a guardrail for the design conception, providing feedback on what is actually possible to construct into a real piece of clothing.

In these beginning stages, when we’re balancing the needs of the stylist and their client against the design heritage of our brand and the constraints of physics and reality of making a piece of clothing, the first sketches are very rough, with pencil. At this stage, we’re just trying to determine if we’re going in the right direction. And we develop from there.

Sarah: When you make these drawings what technical aspects need to be taken into consideration?

Sam: First of all, garment construction is everything. Especially when it comes to fabrication. The same design will look and feel and operate completely differently depending on the fabric you choose to make it in. A taffeta or a chiffon with a tulle fabric will have a completely different volume, lightness, or feeling - and that needs to translate on the page. One of the first things I ask a designer about when I’m making a sketch is fabric. If it’s a taffeta I need to create sharper and stronger lines with my pencil. If I’m doing a chiffon or a tulle, I try to be a lot lighter with my lines to evoke that crispiness or floatiness.

Also when you factor in the digital aspect of things, as at that stage we’ve moved on from a pencil sketch and are doing more formal drawings which are typically done on Photoshop, it can be difficult to find a digital brush that truly mimics the feeling of a handmade brush. An area where this is a really big challenge is in colouring. Recreating velvet or taffeta can be tricky when rendering in digital.

Last, but not least, one of the biggest factors for consideration is the pose.

Sarah: Wow, really?!

Sam: Absolutely! Once you know what’s the potential of a dress, you have to think about the best pose that will let the dress look its best on paper and presented to the client. It’s not just a proposal of the dress itself, but - in our opinion as the designer - how to ‘sell’ the dress in its final form so that everyone looks their best.

Sarah: I’ve always said that so many factors need to come together to make red carpet magic. The gown can fit beautifully, the accessories can be perfect, but the final piece of the puzzle is the person wearing it and what untouchable ‘je ne sais quoi’ human element they bring that makes everything come together and come alive.

Sam: Exactly. So when you’re making that illustration, you have to capture not just how a stylist says they want something to look like but also what they want it to feel like when their client wears it. And a key way to demonstrate that is with the pose of an illustration. Say you’re designing a dress with a slit, of course you’re going to draw the wearer with a pose where the leg is visible. If you have a dress that has a plain front but has a beautiful embellishment in the back or a long train, of course I’m going to draw it at three quarters. Every time I illustrate something, I consider the greatest potential of that garment. How can I sketch it in the best light so that the person who wears it understands how to sell it when they actually have it on?

Every time I illustrate something, I consider the greatest potential of that garment.

For brides, it’s totally different. For a bride, everything is dreamy or romantic or light. That’s why I have prepared a wide range of poses that I have to pick or change what works best for each illustration.

Sarah: There really is an art and a science to every single thing when it comes to fashion, isn’t there? Every single thing is thought of. There’s so much thought that goes into a simple piece of clothing between its conception to when it actually gets worn.

Sam: Especially because a person on a red carpet or event or stage, we try to visualize what is going to happen in the future. We try to get close to the reality of the life that garment is going to live.

Sarah: Walk me through the rest of the process, after that initial brainstorm.

After that initial design phase, a pattern cutter works on draping toiles and calicos [early iterations executed with inexpensive fabric in order to test and perfect a design] so that the client has something to try on in order to understand how the vision is coming to life. It’s at that point that they can provide feedback or offer changes. There’s always changes *laughs*.

In the second stage, we’re updating our sketches and toiles in tandem based on feedback. Sometimes it can be one fitting, sometimes it can be five - or even more. When a toile is finalized and we have the green light to proceed in the final fabric of the garment, I jump back in to present the illustration that gets externally communicated by the brand.

As an illustrator, I am most involved at the beginning and end of a project.

There’s always something that’s changed between the initial sketch and the final illustration. By the end point, we have an understanding not just of the construction of the design but also how the design is going to be presented and styled. What shoes, what jewelry, what hair, what makeup. All of this gets factored into that final illustration.

It’s why I always keep my laptop close to me - for any last minute changes. An illustration has a richer degree of detail and embellishments than an original sketch. It’s like a circle closing at the end.

[An illustration is] like a circle closing at the end.

Sarah: The most common question I get that I of course have to ask you is … why do fashion illustrations look the way they do?

Sam: I get this question all the time, too. *laughs* Fashion illustration aims to make the garment the focal point, showcasing its elegance and appeal. Ultimately, the goal is to highlight the dress itself. To draw attention to the garment, we create more space for it to shine, which often requires a taller or longer figure to wear it, allowing the design to take center stage. At the end of the day, it’s because we have to make the dress the protagonist. In order to bring attention to the garment itself, we need more physical space for it to occupy which necessitates a longer subject that wears it.

In fashion illustration, everything is exaggerated. It’s not a portrait, it’s not a picture. It’s an illustration. It’s an artistic expression of a garment. It’s a little abstract.

S: What is one thing you need people to know about fashion illustration?

Our role is drawing something realistic but at the same time, dreamier. We are artists trying to express and interpret this garment and the designer’s ideas. We’re creating a space to be playful with silhouettes and volume. In fashion illustration, you need to give the feeling of the garment through a drawing translating the designer vision into what it could look like.

In fashion illustration, you need to give the feeling of the garment.

Thank you so much to Sam for her time and expertise. It was such an illuminating conversation on a part of the design process that I find fascinating. I think I could have talked to her for hours about all the intricacies of her work!

This is so neat, Sarah! As an art lover and someone who tries to support artists, I really enjoyed this.